Appropriative photography received the art world sanction in the late 1970s when works by Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince were shown for first time in galleries.

Anyone reading this knows that the use of images sourced from newspapers and magazines has long been a tenet of art. Marcel Duchamp is generally credited as the first artist to present as an art object ordinary manufactured objects. Calling things that he selected and signed “Readymades,” Duchamp tweaked the art establishment of his day by titling a urinal as “Fountain” and signing it with the pseudonymous R. Mutt.

As surprising as the notion of the “ready made” may have in its time, the aesthetic qualities of the chosen objects were sometimes quite manifest in their given forms. Although an assault on good taste, the shape of a urinal is not so shocking as a modernist form, and, presented in an art gallery, this object, unlike many other appropriated elements in art, was actually recontextualized. Although Duchamp claimed to have no interest in the visual form of art, back then, it was possible to see a urinal or a bottle rack as sculptural forms. Because of the functional aspect of these objects and the startling concept they posed at the time, these artworks simultaneously posed and answered the question of recontextualization: Could an ordinary object be seen as an art object? Presented as an object, within a gallery, yes, it can be seen as an art object.” Later, Warhol’s outright reuse of newspaper clippings and commercial imagery to make his paintings along with the comic book imagery of Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings furthered the idea that the visual elements of an artwork did not have to originate with the artist.

So, seeing the work of Levine and Prince for the first time, I thought it easy to see it as a reprise of pop art sensibilities. Regarding their work, I’m not going to get very far arguing against an article of accepted faith. Widely exhibited in museums and acquired by powerful collectors, Levine and Prince’s work has been an inspiration to legions of artists. But the questioning of originality that is raised by Levine and Prince’s appropriated photographs is not particularly deep. Simply put, it goes to the idea, “Are there any truly original ideas in art?” Is this a question that really needs much thought? The problem with this question is that it can be answered in a few sentences. I am well aware that thousands of pages have been written about mediation and simulacra and other post modern jargon. For some it makes for good reading, and for others it’s the pro forma of many a gallery press release. To my mind, making art with the rationale that “there are no original ideas, so why not simply present a copy of another artwork?” can be expressed with the making of just one work. Take a photograph of another photograph and frame it- done. Is the idea further explicated by repeating the exercise of copying other works?

All of these thoughts were stimulated after visiting the Douglas Rickard exhibit at Yossi Milo. Born in 1968, Rickard could be seen as the progeny of Levine and Prince had they produced a child together. Similar to Prince’s early work which were copied from the pages of magazines he perused when working for Time Life Publications, Rickard finds his imagery at one source, Google Street View. The gallery press release describes his methodology: “Rickard took advantage of Google’s massive image archive to virtually explore the roads of America…. After locating and composing scenes of urban and rural decay, Rickard re-photographed the images on his computer screen with a tripod- mounted camera…”

On the first count, the work conforms to Post Modern orthodoxy:his subject is mediated rather than actual. The work also conforms to established traditions of straight documentary photography as pointed out by the press release: “Rickard’s work evokes a connection to the tradition of American street photography, with knowing (italics mine) references to Walker Evans, Robert Frank, William Eggleston and Stephen Shore.”

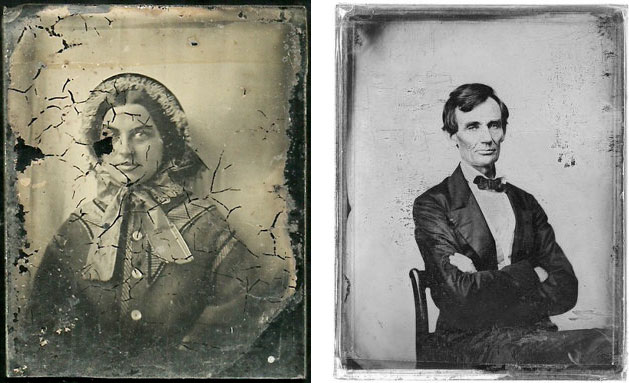

Left: Stephen Shore, Broad Street, Regina, Saskatchewan, 1974

Right: Douglas Rickard, #40.805716, Bronx, NY. 2009, 2011

Left: William Eggleston, Girl in Green Dress Walking Near Minter City & Glendora, Mississippi, 1973

Right: Doug Rickard, #42.418064, Detroit, MI. 2009, 2010

Here, I think, are a few question that have unwittingly been raised by the project:

If a camera mounted on a car can automatically make works so similar to those made by the masters of documentary photography, what does that tell us about the documentary practice? Is there an audience already primed with an interest in “forgotten, economically devastated, and largely abandoned places.” As Shore followed Evans, so too, do many photographers still roam America, searching for ramshackle buildings and dusty roads. For us living in more refined locales this kind of imagery is at once strange and familiar. Such works have become canonical art photographs. By panning through the endless panorama comprising Google Street view, Rickard has picked out photographs that conform to what have become the clichés of documentary photography.

Is Doug Rickard making art or acting as a curator of found art? Is this practice of selecting these images akin to the collector of unusual vintage snap shots found at flea markets? Connoisseurs of found photographs have indeed managed to find extraordinary images that have accidentally achieved some ineffable power. It has long been known that the camera can make a compelling image as much by mistake as by deliberation. Rickard has certainly chosen well and these images generate interest in that the images have the look of documentary art photography.

Left: Stephen Shore, Holden Street, North Adams, Massachusetts 1974

Right: Doug Rickard, #39.259736, Baltimore, MD. 2008, 2011

Left: Walker Evans, Garage in Southern City Outskirts, 1936

Right: Doug Rickard, #41.779976, Chicago, IL. 2007, 2011

At first viewing, the project seems like a clever idea: “Mining” Google Street view for art. But somehow it quickly becomes formulaic. “Knowing” references, connections to the tradition of American Street photography and appropriation, add water, stir, voila- a recipe for today’s art.