A Saturday afternoon (September 22nd) spent at the galleries on 57th Street was satisfying. I saw mostly photo-based work. Four shows inspired my thoughts: Gerhard Richter; Ray Metzker; Sally Mann and Fazel Sheik. My comments will be posted in 3 installments.

Part 1. The first stop was the Gerhard Richter exhibition at Marianne Goodman.

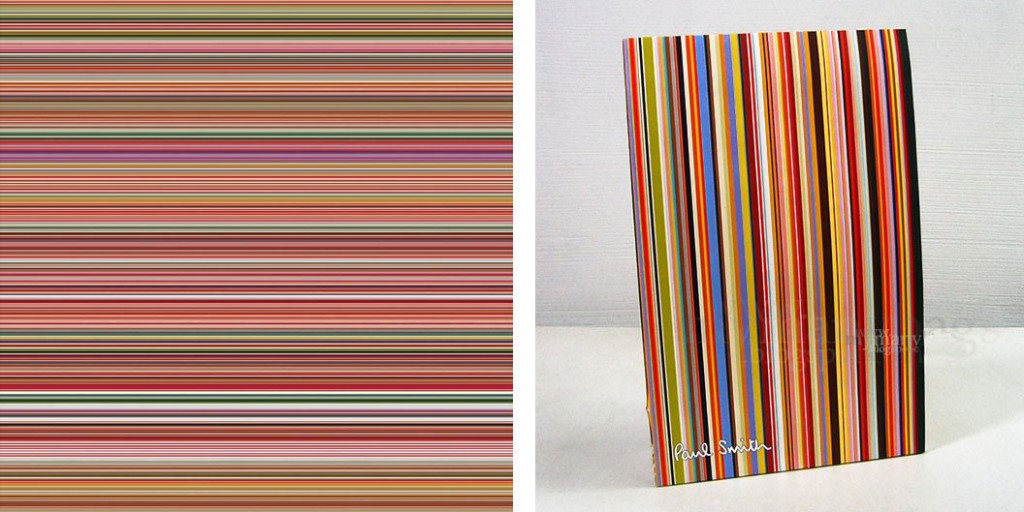

Seen from afar, these large-scale works (the biggest are approximately 7 feet high by 20 long), beckon the viewer for a closer view of their striped surfaces. At times the colossal scale of art found in the realm of the blue chip galleries might be the only distinguishing factor between greatness and mediocrity. In this case, close viewing redeems the work. As I walked closer to each perfect, matt finished panel, my visual field began to vibrate. The press release explains, “Using computer technique to generate digital files, Richter developed “a display of more than 4000 patterns… into an ever more linear pictorial plane of 8,190 refined striations.” Moving still closer, the flatness of the picture plane became decidedly undulant. I approached each work and was rewarded with the same dizzying optical payout. My companion, however, was unimpressed by what she dismissed as Photoshop gimmickry, likening the results to Paul Smith shopping bags. She has a point. When seen at similar scale, what is the difference? I left the gallery with mixed feelings. Is a mere size displacement all that is needed to make art?

Part 2. On view at Laurence Miller Gallery, was Ray Metzker’s Pictus Interruptus series. Metzker’s entire oeuvre, spanning more than 60 years should be known to many readers for crisp, gemlike black and white studies of highlight and shadow as well as multiple frame composite assemblages. The Pictus Interruptus series, dating from 1977 is so unconventional, that I must confess to “not getting it” when I saw them hanging at the Light Gallery back in the day. By 1999, I was able to appreciate what Metzker was up to when I saw Pictus Interruptus (80CQ32), 1980 at Laurence Miller gallery. Seeing a comprehensive selection from the entire series on Saturday, I thought the work to be more inventive than much of the Photoshop based work being produced today. Using only a camera and film, Metzker plumbs the depths of pictorial space. Employing his visual intelligence and awareness of the nature of photographic depiction, Metzker set about to construct abstract spatial illusions.

Some might think that these photographs are about nothing and in fact, virtually no recognizable objects can be seen in these works. These reductivist photographs, depict only tone, line, highlight and shadow, certainly the stuff of abstract photography through the ages. What distinguishes these images is Metzker’s willful defiance of the camera’s optical representation. Considering that cameras are generally used to encapsulate a view of that which it is pointed at, (more or less) the camera preserves that sight. What the camera sees is what we get. Normally, the camera user composes images that are focused and properly exposed. This is particularly so with today’s automatic digital cameras.

The cliché, “Rules are made to be broken” has certainly been the case in the history of photography and innumerable and extraordinary photographs have been made that are not focused or properly exposed-intentionally or otherwise. In this series, Metzker deliberately placed elements such as sheets of cardboard into the field of view of his camera. The elements, placed much closer to the camera than the distance for which the lens was focused do not “render” as objects, instead they obscure much of the what might be contained in rectangle of the image, in effect floating as white or grey diaphanous shapes through which glimpses of properly exposed and focused surfaces can be seen. The out of focus areas and strong diagonals of white and grey juxtaposed against darker, clearly rendered darker textures create a sense of deeper space than that typically seen in photographs. The effect is confounding.

Stay tuned for part 3…

Love it Jan

Pingback: Ken Josephson at Gitterman Gallery | Jan Staller