Barney Kulok’s new photographs ably straddle the two camps in which the medium finds itself these days:

- Photography seen at art galleries- created by artists using photography.

- Photography as seen at photography galleries- created by photographers.

The distinctions between the camps are in many cases fluid, and one can find documentary, straight photography in both precincts. Kulok’s crisp, tonally brilliant black and white prints hearken back to the kind of issues explored by the great modernist photographers- say Minor White or Aaron Siskind. Although their photographs, when first made, were not seen in art galleries, their works were both respected by and influential to abstract painters that were practicing in the day. To this day, though, the finely made black and white print is usually found at photography galleries and these works typically follow the traditions and conventions of black and white photography- typically nudes, landscapes or documentary works.

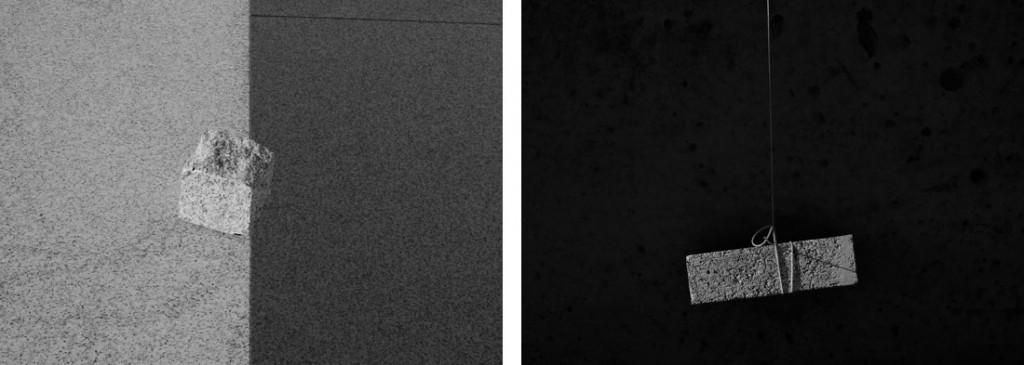

Kulok’s work continues the kind of photography that demonstrates a particular way of seeing. By that, I mean, a photographer whose investigations reveal the hidden within the visible. Not so much overturning a stone to reveal what is beneath, but for seeing the stone as no one else has seen it. And Kulok has literally photographed stone in his own way. Working at the construction site of the Lois Kahn’s Four Freedoms’ Park on Roosevelt Island, Kulok has made striking, formally rigorous images of architectural granite

Barney Kulok. Photos courtesy of Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery

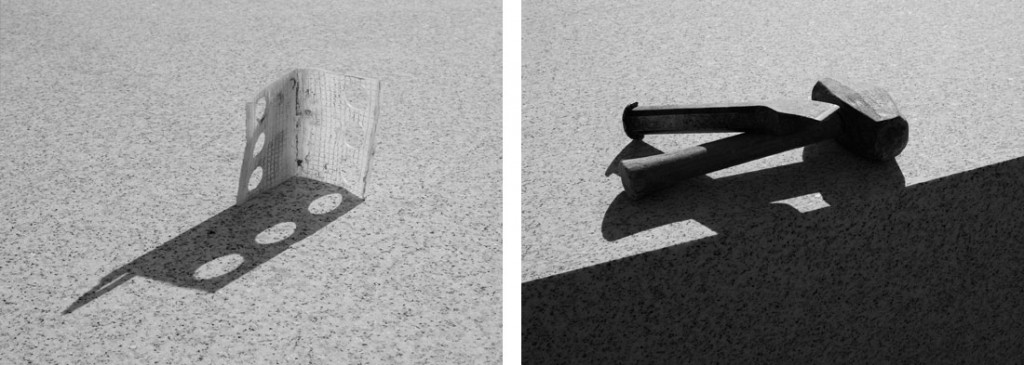

The stark contrasts of traditional black and white photography are employed by Kulok to render his selected elements as reductive compositions. For example a cube of granite poised caddy corner on the demarcation between light and dark that neatly bisects the image. With sensitivity to the expressive qualities of black and white silver print imagery, Kulok sees that light can transform the insignificant. A brick hanging from a string as an improvised plumb bob, when seen in the full color of our vision, would likely have drawn little notice that day. Encapsulated by Kulok’s photograph, the sunlit brick intensely glows in contrast to the shadowed wall it hangs against. With bold shadows and highlights, Hammer and Chisel, avoids the preciousness of a still life composition about humble worker’s tools. To my eyes, Kulok’s pared down and reductive images are more successful than those with greater detail. Images with more content become more descriptive and less transcendent. The subject of “Corner” could not be any more insignificant: an L shaped piece of plastic perforated with six holes set upon a granite surface. Photographed as found, the image demonstrates how photography can elevate the mundane. When rendered in rich black and white tones, substance and shadow invert and the dark grey silhouette cast on the granite creates the illusion of a sheet of dark grey paper bent into a ‘v’ formation floating in space. It’s a puzzling illusion that refers more to painted space than photographed space.

Barney Kulok. Photos courtesy of Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery

In addition to noticing the subtle, Kulok’s admixture of minimalist sensibilities with black and white photography assures the relevance of his work to the precincts of art galleries. These conceptual underpinnings find little currency in photography galleries, where outside of the work of Ray Metzker (see blog) such minimal imagery is seldom seen.