As an artist, I’d like to think that I’m forward thinking enough to accept the many forms and ideas of contemporary art. However, upon walking into Eric Doeringer’s exhibit at Mulherin&Pollard my immediate thought was, “How could this hollow notion be served up again: an art work that is a copy of someone else’s work?

In this case, the artist has copied art that was already a copy of an artwork. A copy of a copy. Among other works, Doeringer’s was presenting his copies of Richard Prince copies of Marlboro cigarette advertisements. It’s the same conceit we saw for the first time in Sherrie Levine’s earliest work, but taken to the next level: if making a copy of art is art, then copying the copy could make another artwork. In a jocular moment, I had the same idea several years ago when viewing “After Rodchenko,” a work “by” Sherrie Levine, which was under consideration for purchase by a museum’s photography committee. In support of this possible purchase, the curator’s presentation pointed out the historical significance of these early appropriated works. Moreover, because the museum had not purchased the work when the prices were lower, she urged the group to buy the work at $80,000.00, before the work became even more expensive. As the group gathered around to examine Levine’s copies of 9 Rodchenko, I took out my pocket digital camera, and after photographing all the images, I mischievously quipped that I would provide copies of the copies for significantly less than $80K.

Left: Sherrie Levine, After Rodchenko, 1987. Gelatin silver print, $15.000

Right: Alexander Rodchenko, Pioneer Trumpeter, 1930. Gelatin silver print, $3995

As I wrote in a previous blog entry, I find little interest in appropriative photography. While I can well appreciate the use of recycled elements of one art to make another art, presenting a direct copy of an artwork as an artwork is one of those art world ideas that seems like a joke to all but art world insiders. Observing the wealthy photography committee members toting their Hermes Kelly Bags, I couldn’t help thinking: Surely they would never purchase a knock off Hermes on Canal Street. Aside from the conceptual rubric, what is the difference between a copy of an artwork and the copy of a handbag?

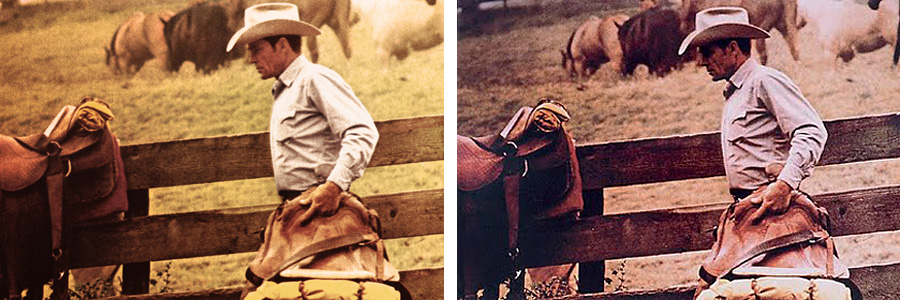

Left: Eric Doeringer, Untitled (Cowboys) 005, 2011. Archival inkjet print, $2200

Right: Richard Prince, Cowboy #1, 1992. Price range: $300.000-1.500.000

As the gallery tells it, “(Doeringer’s) works in this exhibition are all based on pieces originally made by other artists. Doeringer chose to remake these artworks because the originals raise questions of authorship, authenticity, ownership, and the importance of the “hand” of the artist. The artist sees his works as extensions of the earlier works, building upon the conundrums they originally created.” 30 years on, the appropriation gambit, like the press release quote, has become academic. By now, I’d like to think that the art world would move on to newly invented movements. For some, the notion still satisfies: Ken Johnson of the New York Times wrote, “Mr. Doeringer is a late comer to the art-about-art game, a follower in the footsteps of Richard Pettibone and Sherrie Levine. His distinction is his focus is not on canonical works of Modernism but on famous conceptualist pieces that are themselves about art. He is a meta-meta artist.” We can only look forward to a future article praising the artist who replicates Doeringer’s oeuvre.

Not wanting to dismiss an artist based on the impressions of one show, I turned to Doeringer’s website and was amused by a number of the works found there. There is a playful quality in some of his efforts (his satirical Cremaster Fanatic site is very funny), but the “art-about-art game” has become a regular pursuit of graduate students. Of the various projects found on his site, I think one in particular lets us know where the bar has been set: “The Shit Stream.” The artist characterizes this series as “a blog documenting all of my bowel movements…. I was…interested in the idea that feces is like a little sculpture that we create every day.”

This is no more original than any of Doeringer’s other ideas. In Jules Feiffer’s 1967 darkly satirical play “Little Murders,” the main character [played in the movie version by Elliot Gould] is a photographer who takes pictures of shit. Feiffer was pointing out the art world will elevate just about anything into the high realm of Art, a barbed point which is just as true today as it was a half century ago.