I had not been aware of Bob Mizer’s photography until coming across two reviews. After reading them, I headed over to see DEVOTION: Excavating Bob Mizer exhibit at 80WSE Gallery. The press materials notes he was a pioneer in the Beefcake genre of photography. An internet search reveals that these sexually suggestive male nude photographs were distributed primarily through the mail and in the publication Physique Pictorial. While “cheesecake” risque’ nude photographs of women had long been available to stoke the heterosexual male libido, male homosexual desire, being suppressed by cultural intolerance, would have difficulty finding a ready source for homoerotic art and photography. Bob Mizer’s photography catered to those desires.

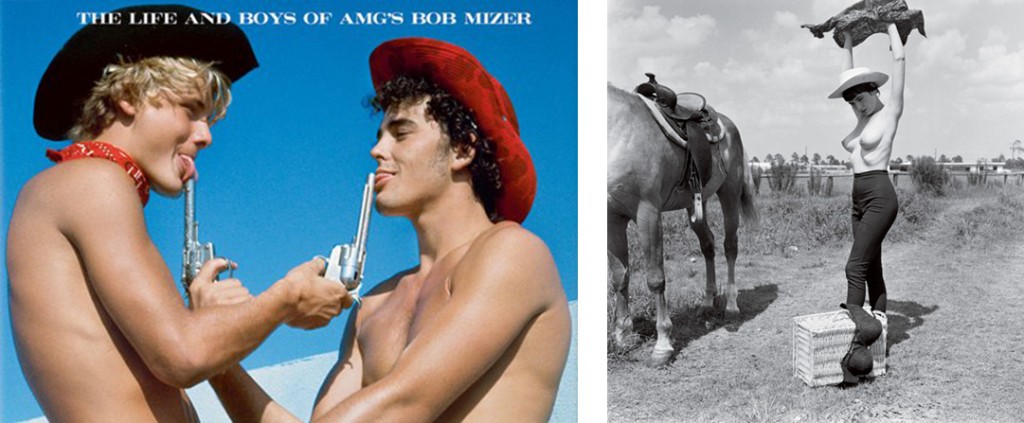

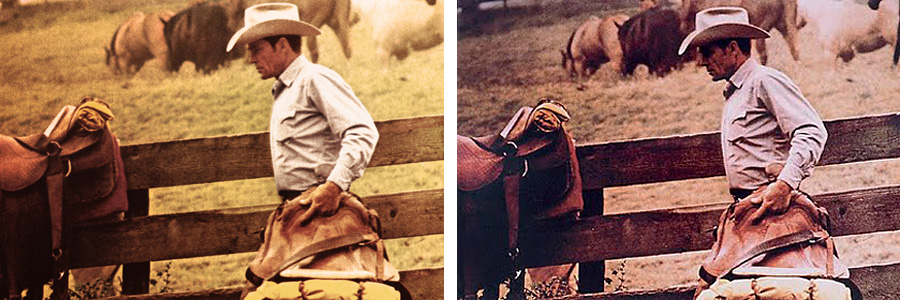

The industry of Bob Mizer is inarguable. He is credited with making 3000 films, and the full depth of his still photo archives has have yet to be fully plumbed. The press release would have us believe that Mizer is an “enigmatic American photographer; arguably one of the most compellingly prolific cultural documentarians of the 20th century”. To my mind, the work hanging in the gallery is neither documentary nor compelling. There’s no enigma, either: the male models pose to reveal as much of their anatomy as permissible by obscenity laws, their genitalia concealed by a g string. Intended to fully reveal the musculature of the body builder models, poses range from stilted to laughable. A recurring motif are buff hunks wearing nothing but cowboy boots and/ or cowboy hats. A variation are two bare chested cowboy-hatted models, self consciously posing face to face while at the same time licking the muzzles of toy cap guns.

The same sorts of props and poses can be found in cheesecake imagery. At 80 WSE galleries, a few ‘conventional’ portraits can be found– and they are simply conventional. Also hanging is a staged photograph of young men working on an automobile. Similar illustrative images could be found in car magazines of the era. Beyond a gay man’s libido, there is little stimulation to be found in Mizer’s work.

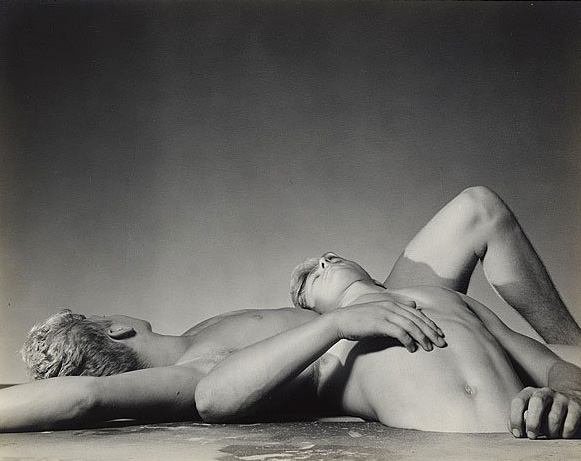

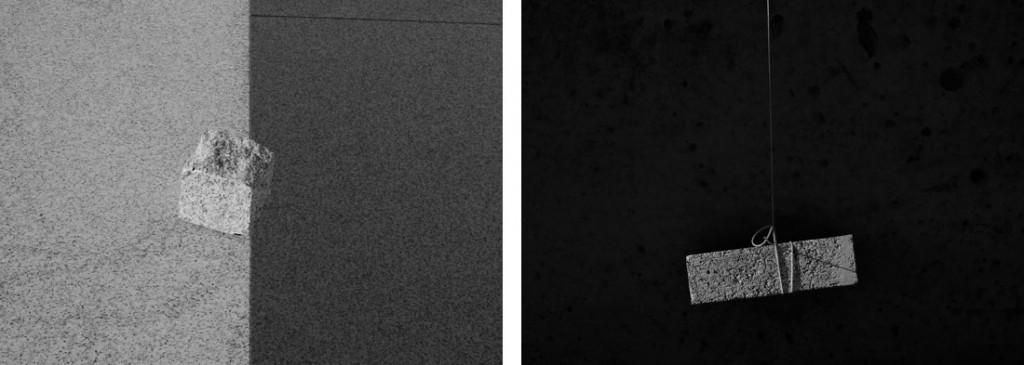

Contrast Mizer’s work to George Platt Lynes: Lynes, an accomplished editorial and commercial photographer who faced the same taboos against homoerotic imagery, albeit at an earlier time. Taking inspiration from classical sculpture, surrealism and avant garde art of the 1930s, Lynes’ men were rendered in rich black and white tones that strongly delineated the male form while at the same time portraying a subtle sexual energy.

That Bob Mizer is being pronounced an undiscovered artist of a bygone era is familiar phenomena of these times. Not to say that the canon is fixed for all time, but in the 150 years since photography’s invention, the works of the great photographers have been widely seen in museums and print. In dredging the river of photographic imagery, connoisseurs of the medium are now serving up all sorts of material made for some illustrative purpose which we are now being encouraged to interpret as art.

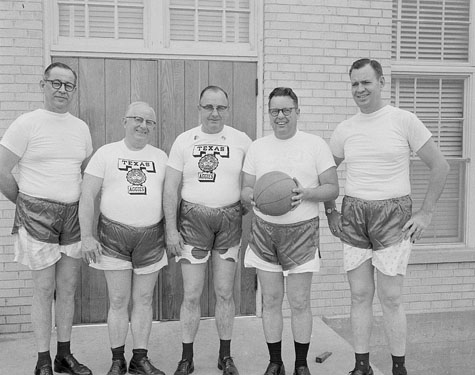

Consider the 2008 International Center of Photography exhibition of a Fort Worth, Texas photographer, Bill Wood, who worked from 1937-73. The images of that show depicted small town events, car dealerships and grand openings of local stores. And there lies the attraction for many of the photographs that are being shown as newly found masterpieces. Whether it be the nostalgic qualities of vintage clothing styles or the stiffly posed studio portraits brought about by the slow and methodical practice of large format film plate photography, old photographs have an undeniable charm. But when made, Wood’s photographs were ordinary and lacked the invention and particular vision of recognized and celebrated photographers of the day. As windows on to another time the images of Wood are quirky and curious. Defined and sensitive interpretations of their subjects, they are not.

Excavating Bob Mizer’s work any further is unlikely to reveal any greater depth than that of typical erotic photography. Today, these mid century nude photographs may seem amusing, but they function on the same level as any pornography and as such there is nothing more than meets the eye.