Part 3. On view at Houk Gallery is a new body of work by Sally Mann. Mann continues with her use of ancient photographic processes, in this case, ambrotype photography. More than a decade ago, Mann began working with the difficult 19th century photographic process, wet plate collodion, producing photographs of Civil War Battlefields with had an emphatically elegiac quality. This feeling was undoubtedly produced by the murky soft focus prints that were characteristic of the wet plate process. Our collective image consciousness knows the brown and grey tone palette of the early photographic processes, and our associations are with the olden days. PBS just broadcast Ric Burns’ Death and the Civil War, a documentary making liberal use of mottled, cracked and blurred glass plate photographs of that tragedy. Mann’s civil war battlefield photographs could be seen as contemporary affectations of those photos.

Since the 1970’s, contemporary use of 19th Century photographic processes has been a pursuit of many photographers. A Google image search of wet plate collodion photographs yields “About 75,300 results (0.36 seconds),” most made in the 21st century, many evoking those same feelings of nostalgia of actual 19th century photographs. In distinction, though, Mann’s practice is highly expressive and evolved.

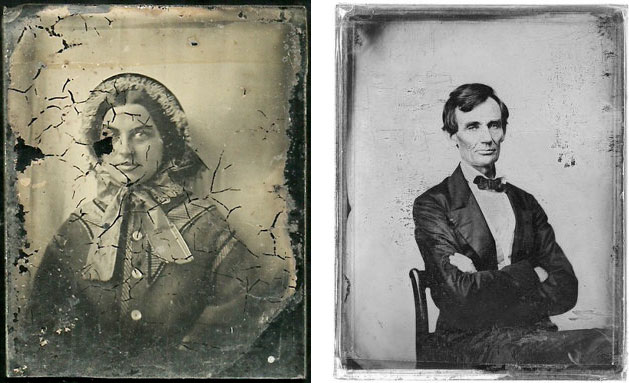

This show is comprised solely of self-portraits. In these works, the technique creates the mood. Like her collodion images, these works are likened in the press release to “discards from a mid-nineteenth-century photo studio – plates flawed by the sitter’s movement or the medium’s unstable actions, of which they present a catalogue: pitting, scarring, scratching, streaking, graininess, blurriness, erosion, fading, haziness, delamination, over-exposure, and under-exposure.” Mann hasn’t simply applied 19th century technique to her contemporary practice; she has reinvented the process by presenting the glass plate images upon black glass instead of clear. She has also applied the 20th century sensibility of seriality to her presentation by arranging multiple glass plates in grids. Clearly inspired by the nostalgic qualities of 19th century processes, Mann has used what would have been considered faults in photographic processing to expressive effect. Her own visage peers out through a clouded, scratched veil of a peeling photographic emulsion. It’s as if we see her face and her torso just behind an extremely dirty window. The effect is one of decay and mortality.

Sally Mann – Untitled (Self-Portraits), 2006-12

At Pace MacGill Gallery, Fazal Sheikh’s work also examines life and death. Traveling far from the cities of New York and Zurich, in which he lives, he has photographed the northern Indian city of Varanasi, located on the Ganges River. Like Varanese, a site that has drawn pilgrims over the ages, India draws westerners to make their pilgrimages in search of visual enlightenment. Notwithstanding their vivid images of a wondrous and unfamiliar land, many are unable to bring back more than scenes from their exotic vacations. The 34 pigment prints on display, Sheikh’s first works in color, have captured an essence in this subject that would have eluded many a photographer. According to the press release, Sheikh seeks to “visualize the spiritual concept of ether…” I found the delicately printed works captivating. It wasn’t until I began writing about the show did I realize how small the actual prints are- 5×7” and 5×7”. These days, we are so accustomed to seeing jumbo prints (I.E. The Richter show) at galleries, it is astonishing how powerful a finely honed artwork can be even at modest scale. Like Sally Mann’s show, Sheikh’s imagery also alludes to death. Very different than the 19th century process of Mann, Sheikh appears to be using advanced photographic equipment and materials. His pigment printing process appears to offer Sheikh a richly expressive palette. The images are somewhat dark and at the same time very luminous. Lacking any noticeable defects, they demonstrate a mastery of technique. As a visitor to the far off land of his subject, it is apparent that he is able to see beyond the obvious Indian exoticism; his observations are sensitive and intimate.

Fazal Sheikh – Either, 2008-2011

Both Mann and Sheikh’s work transport the viewer to a place of their own creation. Mann has photographed herself at home and Sheikh has photographed a more exotic subject, far from home. Mann uses an ancient technique; Sheikh uses contemporary technique. Both artists have recognized qualities of their respective techniques and have distilled singular visions through their deployment.