Is it just me? Try as I might, I just don’t see the genius that is uniformly attributed to the work of Wolfgang Tillmans. In an online search, I thought I might find a dissenting opinion- none were to be found. So here are mine.

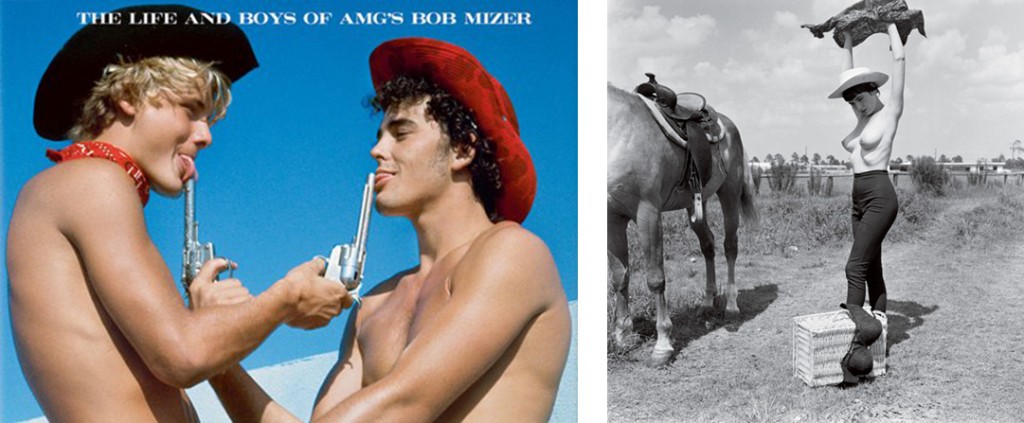

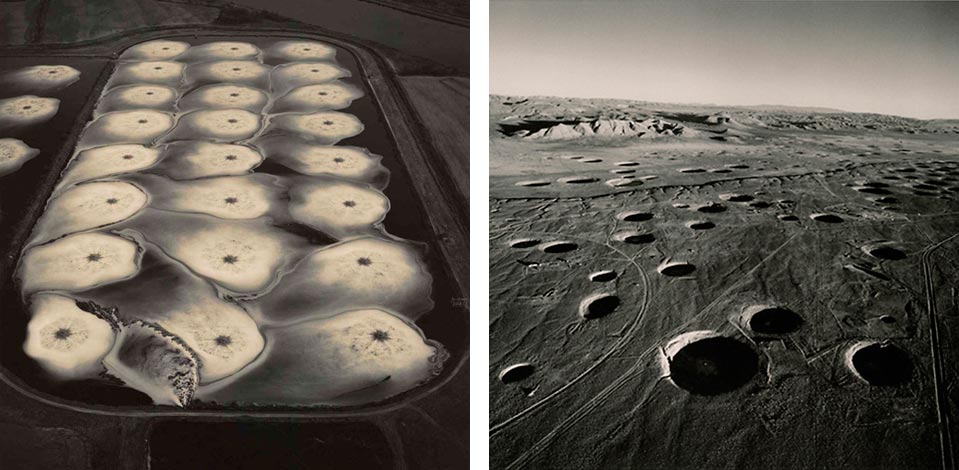

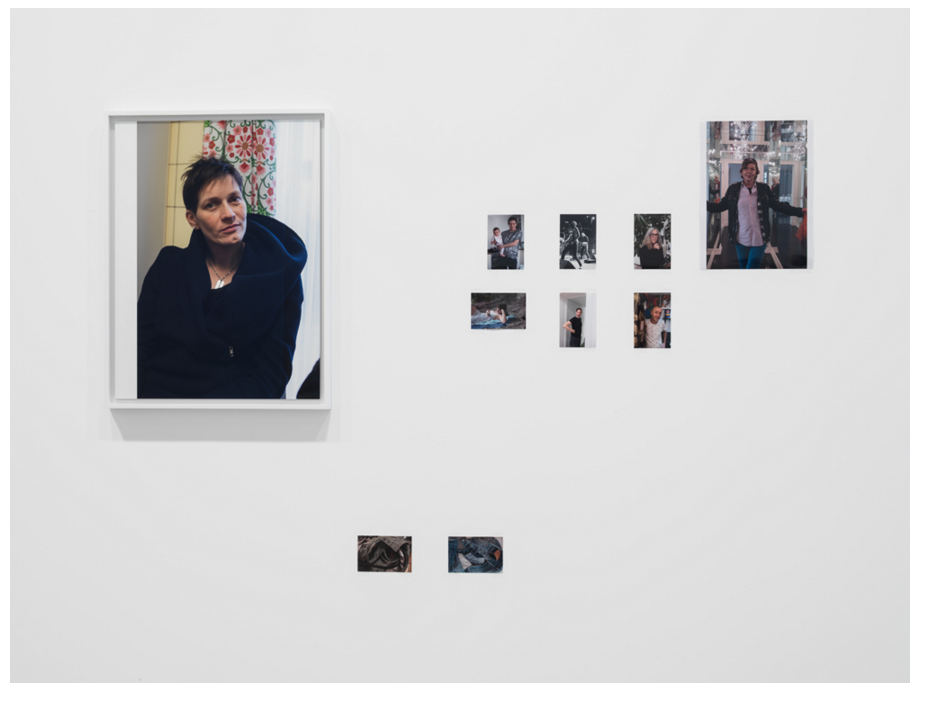

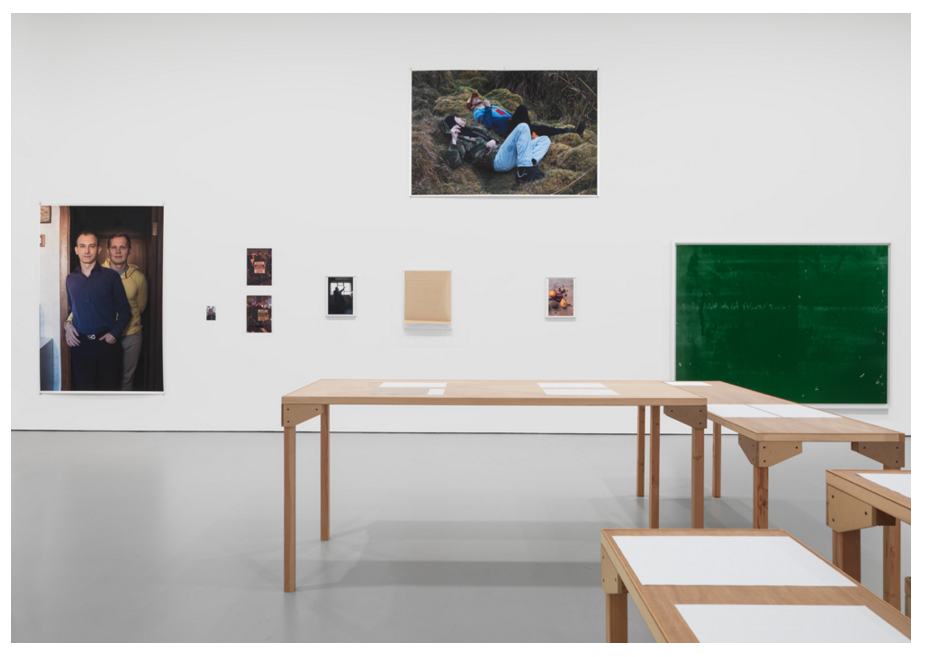

Considering the entirety of his installations, I can recognize the artist’s rejection of the conventions of gallery photograph shows ,i.e., framed prints of uniform sizes. This show appears to adopt what has become another gallery convention, that of contemporary installation art. At its most successful, installation art fills a space with purposely selected and placed objects that direct viewers’ vision to the whole gallery environment as the work rather than to individual objects to be appreciated separately. At worst, an artist densely packs the gallery floor with a jumble of objects, the result: reverse synergy where the sum of the parts is less than the whole. With its motley assortment of variously sized prints, some framed some not, and of no consistent subject matter, a Tillmans’ show is very much in this vein. Respecting the adage about consistency and little minds, I’ll let that go, but what is lacking in Tillmans’ work is the connective tissue, the individual sensibility that a visual artist imprints upon their work. How does one know that an artist has anything to say if the oeuvre shows no particular vision? image from http://tillmans.co.uk/

image from http://tillmans.co.uk/

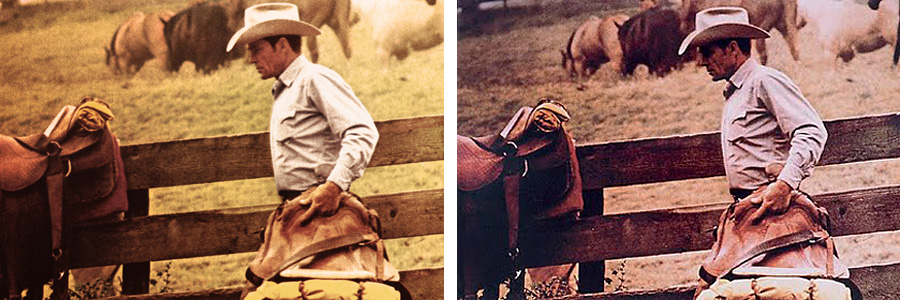

Cameras can faithfully record that which is in front of their lenses, and by virtue of their ubiquity, are going to generate infinitely varied, yet basically descriptive photographs. Cell phone cameras can now make photographs with quality comparable to that of the most technically accomplished and expensively equipped photographer.

Now consider the trope, photography is a language. Spoken language, intelligible to virtually every human for perhaps 60,000 years is rarely the stuff of poetry and literature. By one estimate there are 2.5 billion cameras capable of making technically sufficient images. With assured results and cost free, there are no constraints against making photographs of every g-d thing. The subjects: selfies, genitalia, cats, parties, pranks and the tragedies of war. As do words spoken everyday in conversations, photographs, made of every and anything spill out of cameras incessantly. Utterances may be prosaic or profound- it depends on the minds operating the mouths. On the other hand, cameras are capable of rendering an image of the greatest power and profundity as much by accident as by intention. This is borne out by simply scrolling through instagram where one can find images of genius or drivel from the same user. On occasion, photographs comparable to the most revered images of all time may be seen, but on the whole, the instagram feed is rather humdrum. A user’s brilliant post is likely followed by another banal and unrelated image. With cameras as common as mouths we might do well to distinguish their utterances with the same criteria applied to words, elevating literature from chatter.

Which brings the discussion back to Wolfgang Tillmans: What makes his work special?

Roberta Smith remarked in her review of the show, “Each says what a photograph inevitably says: I was here. And here. And also here.” Exactly the same insights are found on instagram. Smith should be asking, “Why don’t Tillmans’ photographs tell viewers more than the inevitable.” Found at the show are affectless snapshot portraits, pictures of clouds taken from an airplane window, pictures of political gatherings and so many unremarkable photographs of ordinary subjects. image from http://tillmans.co.uk/

image from http://tillmans.co.uk/

Like an instagram feed, some of the photographs in the show intrigue, but most fatigue. Unlike some of the works made without a camera, where Tillman’s inventiveness is evident, the individual photographs, removed from the context of the installation show no particular sensibility or authorship.

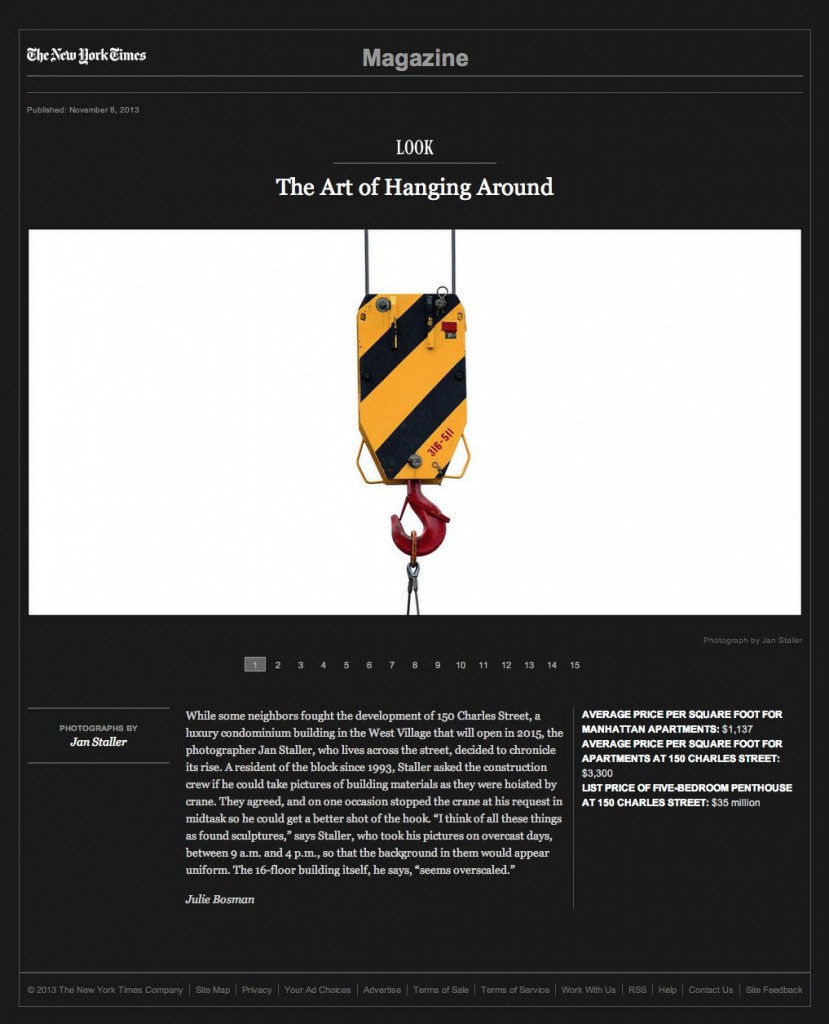

The vast, sprawling scale of the presentation might seem impressive, and for a moment I consider if the show could be considered a single work. But the agglomeration seems gratuitous: why is one photograph small, another large, one framed, another not? Why the spindly wood vitrines? image from http://tillmans.co.uk/

image from http://tillmans.co.uk/

Because the show is comprised largely of photographs, I look at each photograph with an expectation that some visual or conceptual idea is to be found therein. Were the individual images recombined through collage or other technique, their individual importance might be subsumed in the aggregate, but that is not the case here. As with so much installation art seen in galleries: Nothing exceeds like excess!

If any image would be selected to represent Tillmans’ opus it would be “nackt, 2, 2014,” an immense photograph of a man’s buttocks and testicles, to my mind “that taint art.” image from Instagram user @tzyychinnloh

image from Instagram user @tzyychinnloh

Photo credit