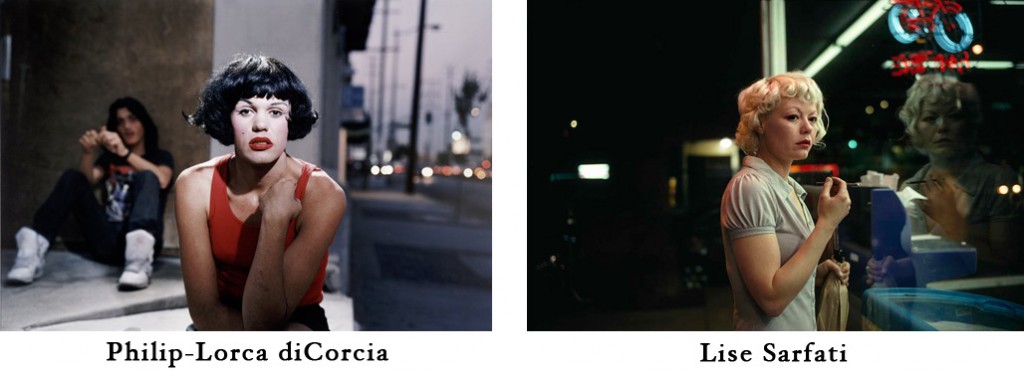

Rineke Dijkstra’s recent show at Marian Goodman Gallery has remained on my mind (June 29 – August 21, 2010 New York). Until this show, Dijkstra’s photographs did not figure large in my pantheon of photography. I found the well-known portrait series of children and young adults at the seaside to offer little sustained interest. The images were an immediate read, utterly factual and heavily referential to art historical precedents. Her photographic technique dates to the time of August Sander and her results except for being in color and of contemporary individuals were very similar to his. Many photographers who have worked with a 4×5 or similar view camera end up making portraits that have a studied awkwardness like those of Sander. This is a function of working with this type of camera, and very few photographers are able to make images that significantly depart from the qualities that are identified with Sander’s work.

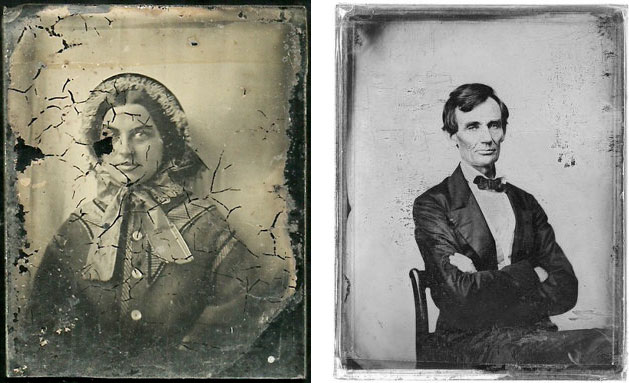

Some may question a reference to Sander’s work without going into detail about the thematic underpinnings of his study of contemporary Germans or how the images were different than the practice of his contempories, but I am limiting the discussion to the characteristic nature of his work . With the 1969 Exhibition of Sander’s work at the Museum of Modern Art, many of us were astonished by the strikingly evidentiary nature of his photography. Part of that had to do with the time capsule nature of old photographs- the quaint costumes and accouterments of another era, but the other aspect was that in the decades since Sander’s time, many more people were being photographed with hand held cameras by friends and family and in those photos people generally looked much more relaxed and casual than those who had to set still for a portrait in Sander’s day. Seeing Sander’s photographs brightly illuminated on the white walls of Moma further heightened the impact of their starkly rendered factuality. Large format straight document was one of the photographic views of the world being championed by Moma. Along with Sander, the photographs of Walker Evans and Atget which were also shown at the time. These shows were very influential for contemporary photographers, and quite a few rejected the practice of handheld 35mm cameras in favor of working with large format cameras and tripods.

For those who haven’t used this kind of equipment, I will attempt a short summary of their relatively complex operation: Most 4×5 cameras do not have viewfinders and so the photographer must put his or her head beneath a focusing cloth (other viewing aids are available which can be substituted for a focusing cloth). It can take several minutes for the photographer to: 1. frame the subject, 2. focus the image, 3. close the lens of the camera and cock the shutter, 4. load the sheet film holder, 5. remove the dark slide on the film holder. While all of this is going on, the sitter must remain fairly still so as not to disturb the composition, focus and sharpness of the image. This would be the time when the photographer may try to influence the sitter’s pose and expression. After all those steps, the exposure is made. For the subject sitting or standing with little to do but uncomfortably stare back at a big box with a single glass eye, large format portraiture can feel like a medical examination. This procedure tends to insure that the sitters have solemn, dignified and stiff countenances rendered in exceptional clarity, very much like the faces in Sander’s portraits. It’s why so many images made by Joel Sternfeld, Alec Soth, and others are very much alike. Besides the individual appearances of their subjects, I didn’t think that many large format portraits images are strongly differentiated from one artist to another. That is, until Dijkstra’s last show.

Instead of using a still camera, Dijkstra has mounted her video camera(s) on a tripod. Of course, making filmed or video portraits has been practiced by other artists, including Andy Warhol. These video portraits merely added monotony to the results by extending the awkward confrontation between camera and subject beyond the few minutes normally involved and also extending the time required to view the work. Little more was yielded by the extra time.

Dijkstra inventively sidestepped the tedious nature of the filmed portrait by making her works actually cinematic. For the video, Weeping Woman, three cameras were mounted on low tripods upon which was affixed a reproduction of the Picasso painting, Weeping Woman. Facing her video setup are nine fresh faced, young, teenage boys and girls. The camera was allowed to roll without interruption for 12 minutes. With this work, Dijkstra has brought portraiture to a whole new level. Whereas her large still portraits describe similar likenesses of awkwardly self-conscious individuals, her video presents 9 exquisitely detailed specimens for us to observe for an extended interval.

In using the Picasso painting as distraction from the camera and videographer, Dijkstra effectively absented herself during the filming and the sitters were able to forget that they were being filmed. Being under the observation of three cameras, would likely make most people self conscious, but these children, dressed in their school uniforms, are preoccupied with a discussion that they are having about the painting.

With this work Dijkstra has created a beautifully voyeuristic experience for her audience. The high definition video spools on allowing us to stare at the expressive faces of the children, something we might wish to do in life, but would not for fear that our intense gaze would be noticed. At best, a still photo might capture a single expressive moment, but in this video, expressions and feelings fleetingly cross their nine faces. It’s as if we are watching time lapse films of weather patterns: furrowing brows, pursing lips, and narrowing eyes animate these nine fascinating faces. We can listen in and we can scrutinize 12 minutes of a life infused group portrait. Their expressive intensity and rapt concentration reminded me of Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lecture of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp. In that painting, he portrayed the very expressive faces of eight surgeons and one corpse. In viewing the video Weeping Woman, we might imagine that if Rembrandt stood in place of the video cameras, he could have chosen from each face of the children one momentary expression from which to make a painting of this group. The experience Djkstra is truly a breakthrough in portraiture.

Similarly Dijkstra’s Ruth Drawing Picasso (approx. 6 minutes) examines a young teenager at the Tate Liverpool sketching a Picasso. In her school uniform and sheepskin boots she sits on the floor, a sketch book in her lap, her face looking up over the camera and then down at her book while intently drawing what we can assume is the Picasso on the wall behind the stationary camera. Scarcely moving, Ruth becomes an analogue of the artist’s model. She sits very still, while the video camera renders her image. It is Ruth’s intense focus that makes the video so engaging. It is the great accomplishment of this artwork that its viewer can remain interested in watching a person quietly sit in place for six minutes.

By contrast the videos of club patrons at The Krazyhouse, Liverpool UK (Megan, Simon, Nicky, Philip, Dee), 2009-2010 are not nearly as evocative. Perhaps studies in self-conscious posturing, the videos seem much more like Dijkstra’s still photographs, only animated. These videos are of young adults slowly dancing and gyrating to cheesy dance music. In one, the dancer is more talented and inventive, and this made this video more interesting than the other three. But all of the videos seemed bound in their specificity. Despite showing much more ‘action’, these video evoke much less feeling. Neither the subject nor the photographer had transcended the process, and the results feel inert. Compared to the keen observation of her young subjects, there is a monotonous and listless quality to the portrayals of the dancers.

In many of Dijkstra’s technically adept still photographs she seems unable to bring more than simple observation to the subject. In her work, the process of photographing and being photographed seemed to impede the evocation of anything more than awkward likenesses. The genius of her video studies of the school children is in the observation of her subjects’ observation. In turn, Dijkstra has acutely studied their intense attention to something outside of themselves. By doing that, she has portrayed something far richer and surprising than her still photographs. Also, by allowing the video camera to run more or less unattended, she took herself out of the process, and in doing that, she invested the results with more of herself than ever before.

The show is accompanied by prints of the same subjects. At best, they are well-chosen film stills, but feel more like souvenirs than the fully formed works that the videos are.